Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

“As spiritual practitioners, we must develop three qualities in our hearts to eliminate the three poisons. With compassion, we can eliminate anger (aversion). With giving, we can eliminate greed (attachment). With wisdom, we can eliminate ignorance. To cultivate these three qualities, we must practice mindfulness.”

Dharma Master Cheng Yen

Dharma Master Cheng Yen consistently ends each teaching with a reminder: “we must always be mindful!” or “everyone, please always be mindful!” One could say that mindfulness is the essence of Buddhist practice. The original terms that have been translated into English as “mindfulness” are sati in Pali, and smṛti in Sanskrit. Their meaning incorporates “to remember,” “to recollect” or “to bear in mind,” alongside “awareness” or “attention” in the present moment.

Other terms are also linked to mindfulness in the Buddhist sense, one being sampajañña (Pali; Sanskrit: saṃprajanya), which means “clear comprehension” or “introspection,” and includes the aspect of being “fully alert” with “focused and concentrated attention.” When sati and sampajañña work in concert with atappa (Pali; Sanskrit: ātapaḥ), meaning “ardency,” the three encapsulate “appropriate attention” or “wise reflection” (Pali: yoniso manisikara; Sanskrit: yoniśas manaskāraḥ).

The term appamāda (Pali; Sanskrit: apramāda), whose meaning is associated with “vigilance,” “diligence,” “concern,” “earnestness” and “restraint,” is also related to mindfulness, and praised in the highest terms in scriptures as the “foremost treasure.” It refers to conscientiousness as to what should be adopted and what avoided, and points to the ethical foundation of mindfulness, which includes keeping the moral precepts and being prudent so as to cause no harm.

Appamāda also concerns “guarding the gates of the senses” and not being obsessed by agreeable or disagreeable sensations. The root “māda” means “drunkenness,” with the emphasizing prefix “pa” it becomes “blind drunk,” but adding the negative prefix “a” in front creates the opposite meaning. The goal is to neither be intoxicated nor seduced by sensory experience, but to remain diligently watchful, with vigilant clear awareness. Appamāda (with the suffix “ena,” meaning “through”) was among the Buddha’s last words, revealing its importance:

“Vayadhammā saṅkhārā appamādena sampādetha.” (Pali) “All things are disappointing, [it is] through vigilance [that] you succeed."

Mahāparinibbāṇa Sutta

Mindfulness is the first among the Seven Factors of Enlightenment (Pali: satta bojjhaṅgā; Sanskrit: sapta bodhyanga), the others being: investigation, energy, joy, tranquility, concentration and equanimity. It is also one of the mental faculties that are known as the Five Spiritual Strengths (Pali, Sanskrit: pañcabalāni), the other four being faith, persistence, concentration and wisdom. And, Right Mindfulness is part of the Noble Eightfold Path that the Buddha taught as the Path to the Cessation of Suffering.

In the Satipaṭṭhānā Sutta from the Pali Canon (Sanskrit: Smṛtyupasthānā Sutra), the Buddha provides detailed instruction on the four foundations of mindfulness.

“This is the only way for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the extinguishing of suffering and grief, for reaching the right path, for the attainment of nibbāna [Pali; Sanskrit: nirvāṇa, meaning liberation]: namely, the Four Arousings of Mindfulness.”

Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta

The practice, which should be done while “ardent with awareness” and “having removed craving and aversion towards the world,” consists of observing, both internally and externally, the following four objects:

Body (Pali; Sanskrit: kaya):

- Including respiration; positions and postures; impermanence of actions; repulsiveness and impurities; material elements of composition; and stages of decomposition after death.

Feelings or Psycho-physiological sensations (Pali; Sanskrit: vedanā):

- Which are classified into three kinds – pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral – and can be experienced with or without attachment.

Mind or thinking (Pali; Sanskrit: citta):

- Which can be associated with craving, aversion or ignorance; collected or scattered, expanded or unexpanded, surpassable or unsurpassable, concentrated or unconcentrated, freed or un-freed.

Mental contents – Buddhist doctrine (Pali: dhamma; Sanskrit: dharma):

- Namely, the Five Hindrances to practice (sensual desire, ill-will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and worry, and doubt); Five Strengths (mentioned above); Five Aggregates of clinging; Six Internal and External Sense Bases (sight and material forms, hearing and sounds, smell and odors, taste and flavors, touch and tactual objects, consciousness and mental objects); Seven Factors of Enlightenment (mentioned above); and Four Noble Truths.

The instruction is to establish awareness with the understanding that “[this] exists to the extent necessary just for knowledge and remembrance,” thus maintaining an attitude of detachment, dwelling “without clinging towards anything in the world.” Direct experience and thorough understanding of impermanence (Pali: anicca; Sanskrit: anityatā) also play a critical role, as one “dwells observing the phenomenon of arising and passing away” with regard to body, feelings, mind, and mental contents.

As Master Cheng Yen reminds us daily, the aim of practice is to be mindful at all times and in everything we do, thus cultivating wisdom, while strengthening our ability to choose wholesome actions of body, speech and mind, and weakening the grip of heedless unwholesome responses. In each moment, we should contemplate:

Did we take good care of our heart? Have we looked after our mind? Where is our mind now? Has our mind wandered outside? Or is our mind focused on our body? Or on our mind itself?

To take care of our heart and mind, the best focus for our mind is our mind itself – that is, to look within, at our inner mind. The Buddha’s innumerable teachings ultimately all take us back to our mind. It is in cultivating the mind that we can access the Dharma and awaken, gaining insight into the truths all around us.

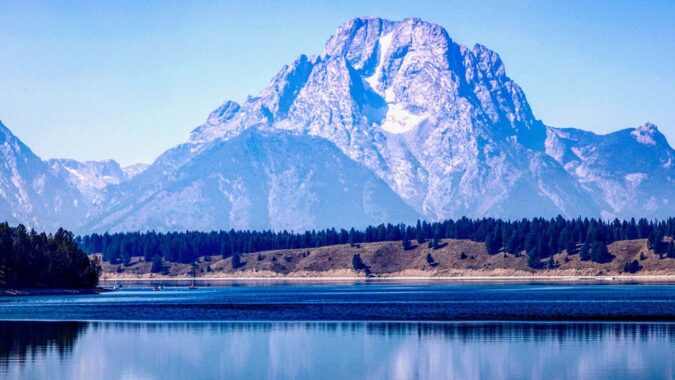

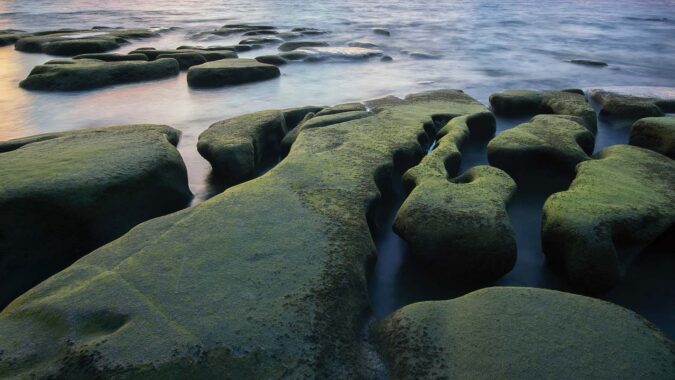

Truth is out there all of the time, but its richness and wonder are often invisible. All around us, everything is operating based on laws and principles. Everything we encounter in this world is a coming together of many elements. The existence of everything wondrous. So miraculous is the wonder of existence that it is often beyond our understanding or imagination.

The Dharma is deep and profound, but at the same time, it is in fact part of our everyday life. With a heart of sincerity and reverence, we can discover the Dharma within our everyday life and begin to see the wonder in the world. So, we need to be mindful in keeping our hearts always on the Dharma. Then, naturally our actions will always be correct and in line with the Dharma.

We need to treat everything with the utmost respect and sincerity. Having a heart of sincerity and reverence will allow us to see the deeper principle in things and elevate our wisdom. This opens and expands our hearts, making us more tolerant, understanding, happy, and capable of overcoming afflictions. We want to let go of afflictions so we can always abide in a peaceful mindset.

As we go about our everyday life, are we joyful and understanding toward everyone and everything? Do we face everything with a genuinely sincere and respectful attitude? We interact with people every day. In these interactions, we need to be tactful and considerate, very mindful of our manner, attitude, tone of voice, gestures and actions, so as not to harm or hurt anyone in our dealings.

When on the receiving end of others’ manner, attitude, tone of voice, etc., the practice is to keep a positive mind and a heart of simple goodness. With such a heart and mind, we will interpret things in a wholesome way and not react negatively or badly.

This is what we need to practice mindfully – learning to see in everyday life the wondrous principles of Dharma at work and to face all people and matters with a sincere and reverent heart. Please, do practice mindfully to keep a sincere, reverent heart always, toward everyone and everything.

The sections in italics consist of edited excerpts of material compiled into English by the Jing Si Abode English Editorial Team, based on Dharma Master Cheng Yen’s talks.